4 Tips to Modernize Your Novel's Grammar

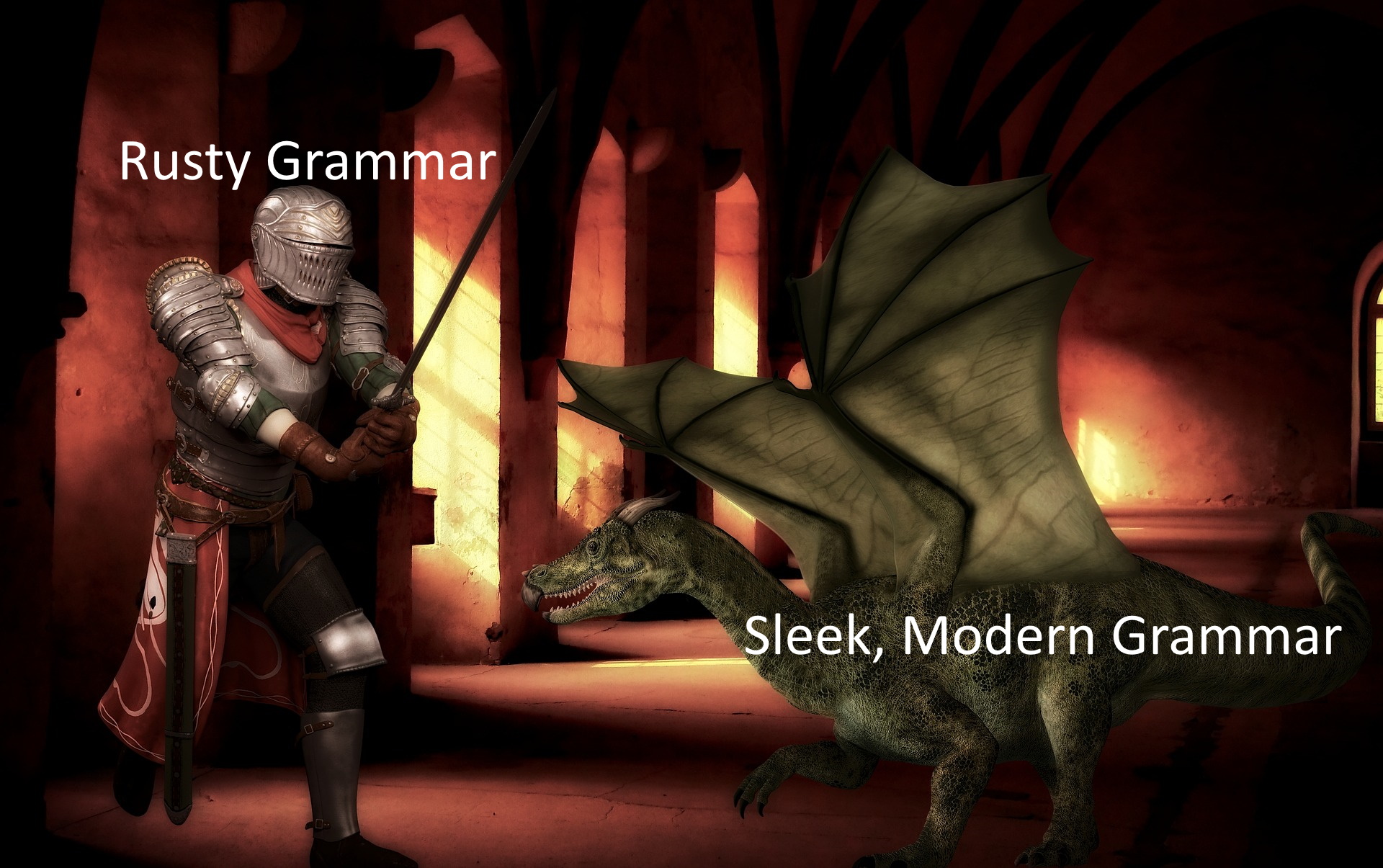

Many people prefer more conventional styles of grammar and language, and that's just fine. However, some authors (and audiences) prefer more modern styles. Whether you are looking for the latest in grammar usage or just seeking new ideas to improve your writing, consider these tips.

Minimalistic Dialogue

You have likely heard the platitude that "Less is More." While not always true (I certainly prefer $1,000 over $10), the principle has valuable application to dialogue. Newer authors love to tell the reader what is happening, how things are said, what characters are feeling, etc. However, when dialogue is simplified to remove this excess information, skilled authors can amplify the effect of the dialogue and speed up the pacing of a scene.

Consider the following example:

Traditional Dialogue

"Pass me that turkey or I will do terrible things to you," Bob said sharply.

"It's all mine!" June replied tersely. "You forgot the cranberry sauce, so I don't have to give it to you."

"Give me a break," he said, anger rising in his voice. "You're always trying to control our family parties. Just let us enjoy Thanksgiving."

"Over my dead body," she replied with fire in her eyes. "Come and get it!"

With that call to arms, Bob leapt on the table and launched himself towards June.

Although the above is grammatically sound, the constant interruptions of the dialogue with dialogue cues ("June replied tersely," "anger rising in his voice") slows down the scene. Although it is relevant that Bob was angry and that June's eyes were ablaze, good authors will communicate such information with the dialogue itself. Show, don't tell.

Here is the same scene without the dialogue commentary:

Modern Dialogue

"Pass me that turkey or I will do terrible things to you," Bob said.

"It's all mine!" June replied. "You forgot the cranberry sauce, so I don't have to give it to you."

"Give me a break. You're always trying to control our family parties. Just let us enjoy Thanksgiving."

"Over my dead body. Come and get it!"

With that call to arms, Bob leapt on the table and launched himself towards June.

Did you notice the improved pacing? Not only that, but you can still feel the conflict without being told that Bob or June are getting increasingly angry. This is not to say that all dialogue cues are bad. The modern example may benefit from a little more description as to how the first two lines were spoken. However, be sure to avoid telling too much. Dialogue between only two people does not require identifying the speaker every line. Give it a try and see if it improves your writing.